Photo by Adarsh Bhat | A rundown sign sits outside the Medicaid Center in San Juan.

By Ilana Gersten

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico – Albert Figueroa recently turned 26, which means he’s been removed from his mother’s health insurance and is now on the hunt for his own. As an Uber driver in San Juan, Figueroa makes roughly $12 an hour, which he says is not a livable wage. Yet Figueroa has been told he makes “too much” to qualify for Medicaid, a federal healthcare program meant to provide insurance for those who can’t afford it.

Figueroa, who asked to be identified by his middle and last names to protect his privacy, applied for Medicaid but was rejected. In fact, for six months, he called again and again to plead his case to no effect. In Puerto Rico, if you make more than $7.25 an hour, Medicaid is likely out of reach.

“When people are so insistent on getting healthcare,” Figueroa said, “it’s because they need it at the moment.” Figueroa doesn’t want to find himself in a position where health insurance is a necessity, yet that is where he’d be if he had a medical emergency.

This and many other problems related to health care on the island of Puerto Rico stem from the same issue: a lack of funding for Medicaid. With 1.5 million citizens already on Medicaid in Puerto Rico – nearly half its population – and many more desperate to qualify, the need for adequate funding is obvious to everyone from residents to health care advocates. But without support from Congress to secure a consistent budget, the likelihood of that happening is slim.

“Much of the structural weaknesses in our healthcare system are directly associated with the financial weakness arising from the underfunding of the Medicaid program,” said Jorge Galva, the executive director of the Puerto Rican Health Insurance Administration, known as ASES in Spanish, a government organization that implements and manages contracts with insurers and health services organizations.

Because Puerto Rico is an official territory of the U.S. and its people are considered U.S. citizens, it receives Medicaid funding. However, because Puerto Ricans don’t pay federal income tax, there are vast differences in how they are treated compared to the citizens of the mainland States.

Photo by Elisabeth Hadjis | Edna Marín, the executive director of Medicaid, speaks to college students about the struggles Medicaid is facing in Puerto Rico

Edna Marín, executive director of Medicaid for the island, is consistently traveling to D.C. to negotiate for the funding her island needs.

“I’ve been in Congress, flying to Congress lately, I will say I’m flying out like every three to four weeks. I’ve been there on a monthly basis for the past year,” said Marín. “And there is an actual administration slogan, that is asking for parity.” In this case, asking for parity means asking for Puerto Rico to be treated the same as a state when it comes to Medicaid.

How is Medicaid funded?

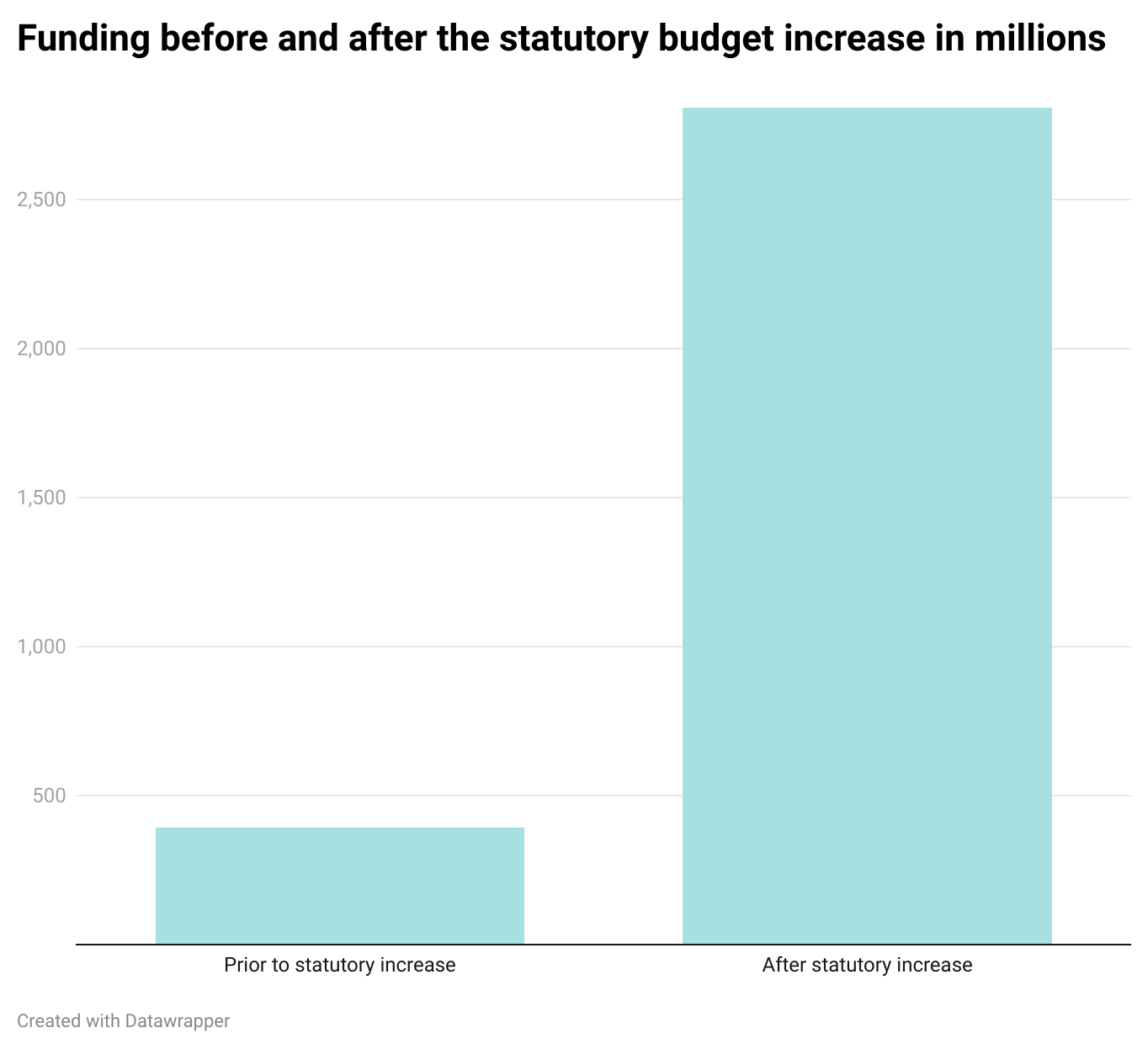

Medicaid is funded through both the state (or territory) and the federal government. States are limited in how much the federal government will provide based upon their average income. However, for territories of the United States, their federal matching rate is fixed and their maximum budget is capped. Before 2021, the budget cap for Medicaid in Puerto Rico was only about $400 million. In September 2021, members of the Biden administration interpreted a statute to permanently raise Puerto Rico’s Medicaid budget. This statutory interpretation raised the cap from $392 million to over $2.9 billion.

To put that number into context, states that have a similar number of people on Medicaid – in this case, 1.5 million – and have a similar per capita income – in this case, $13,318 – have a budget closer to $4 billion annually, 10 times Puerto Rico’s previous limit. The drastic increase to $2.9 billion is a start to resolving many of Puerto Rico’s healthcare issues. Also important to the equation is that the income cap to qualify for Medicaid has been raised, leading to more people becoming eligible.

“The story of Medicaid is a story of chronic underfunding since the inception of the Medicaid program back in the ‘60s. Puerto Rico, unlike the States, has received a capped amount of money,” said Galva.

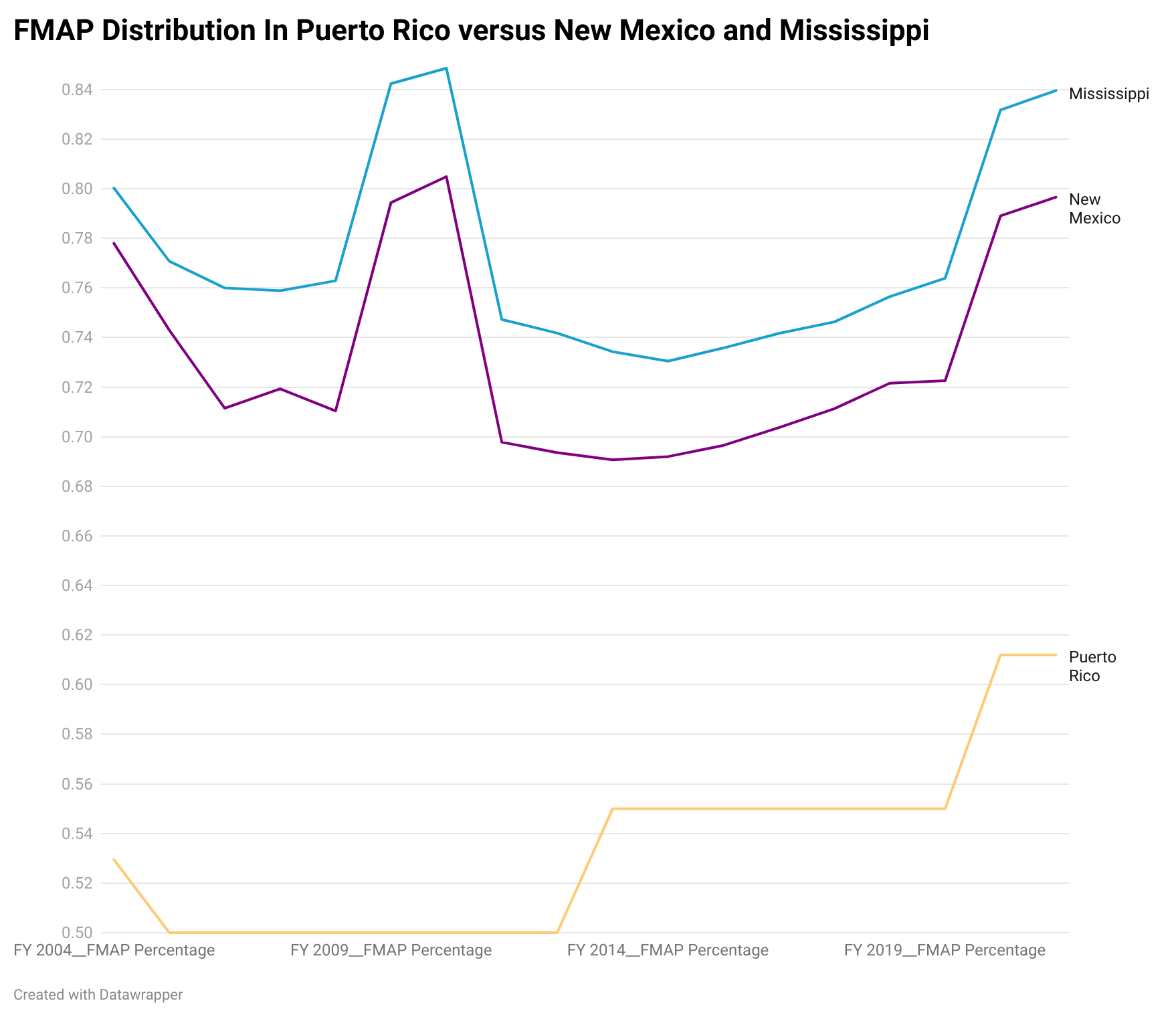

To pay for Medicaid, the federal government uses the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) to determine how much money is provided to each state and how much the state or territory must provide on its own. For most states, FMAP money provides up to 83% of the funding for their Medicaid programs, with states responsible for providing the rest.

But Puerto Rico’s proportion of FMAP is typically capped at just 55%. Recent legislation enacted due to COVID-19 allowed for a temporary FMAP increase to 76%. However, it will revert back to 55% in December 2022.

To better understand the uneven numbers, consider these comparisons: New Mexico is currently the state with the highest percentage of people on Medicaid at 43%. (About 46% of Puerto Ricans are on Medicaid.) Yet New Mexico’s FMAP contribution is 73%. Mississippi is the state most similar to Puerto Rico in terms of per capita income, at $25,444, which is still more than $10,000 higher than Puerto Rico’s. Yet its FMAP has ranged from 73%-83% over the past decade, more than 50% higher than Puerto Rico’s.

“If you were to use the formula they use with the States and it was based on per capita income, for example, Puerto Rico’s should be higher, close to that 83%. That’s the maximum allowable one,” said Lina Stolyar, a Medicaid policy analyst for the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on national health problems.

There’s another figure critical to understanding the calculation: the income cap. In most mainland states, the income cap is based on the federal poverty level, when an individual makes only $13,590 annually.

In Puerto Rico, however, the income cap is based on the island’s poverty level – which is approximately 85% of the federal poverty level. That translates to this: A single person in Puerto Rico would need to make less than $1,247 a month to qualify for Medicaid. In the mainland U.S., that same single person could make $1,506.25 a month – almost $260 more – and still qualify for Medicaid.

When the budget was increased in 2021, one of the first things the money was used for was lowering eligibility requirements so people who made slightly more money, in this case, $7.25 an hour, could qualify. Before the additional funding came through, people making as little as $600 a month made too much to be eligible for Medicaid.

“You don’t have to make them choose between keeping their low salary job and losing the benefits of being covered by Medicaid,” said Galva. “Now you can keep your job and still be insured by Medicaid.”

The bad news is that even with the increase, there’s not enough to cover all of the 17 mandatory benefits Medicaid requires, including inpatient hospital services, physician services and transport to medical care. It costs approximately $1.2 billion just to fund the mandatory benefits, according to Marín, which is nearly 40% of the recently expanded budget.

Judy Solomon, a senior fellow and the interim program area lead for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a non-profit research and policy institute based in Washington D.C., studies how to make health care – and Medicaid specifically – more accessible for low-income people. While Medicaid is required to provide healthcare for people below a certain income limit, Solomon notes that despite the requirements, even for those enrolled in Medicaid in Puerto Rico, it doesn’t provide full coverage.

“In the States, there’s mandatory groups that have to be covered. There’s also mandatory benefits that have to be covered,” said Solomon. “The territories” – including Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the Virgin Islands and the Northern Mariana Islands – “have not been held to those same standards primarily because they’re not being provided the funding that they would need to do that.”

Of the 17 mandatory benefits required, Medicaid in Puerto Rico is missing at least three, including long-term services and supports and nonessential medical transport. These programs cannot be added until there is money to pay for them. These items are expensive, and while they are on the to-do list of Medicaid professionals, the priority has instead been making sure as many people who need Medicaid can get on it.

“I think Puerto Rico would have today, probably about a seventh of what it needs in federal funding,” said Solomon.

Despite the improvements, Marín and Galva worry that the increased budget will be taken away, because some areas of the U.S. government, including the Government Accountability Office, don’t agree with the current interpretation of the statute. Also, when a new person comes to power in the United States, or if the party in power changes, it’s possible they could have a different interpretation and the funding would revert back to $400 million.

“It’s really hard to plan around uncertainty any planning budget to be executed. If we don’t have a budget, it’s really hard to plan on a short, mid or long term,” said Marín.

For his part, Galva has grown frustrated with the debate over whether or not Puerto Ricans deserve the funding since they do not pay federal income taxes. To him, that is no excuse for them to not have a properly funded health insurance system.

“OK guys, so you’re a territory and you don’t pay federal tax income taxes. Why should you get parity in terms of the funding? And the reply to that is because we’re American citizens, and we’re supposed to be treated equally,” said Galva. “And that includes access to health care, which is one of the critical services provided or funded by the federal government.”

No matter how hard those in charge of health insurance on the island advocate for the federal government to provide them with more money, they are facing one giant hurdle: They do not have a vote in Congress. Puerto Rico’s only representation in Congress is the “resident commissioner,” Jenniffer Gonzáles-Colón, who is a non-voting member. That leaves the fate of funding Puerto Rican programs in the hands of representatives from other states who tend to prioritize their own constituents over the needs of the people of Puerto Rico.

“It’s a very, very uphill battle because you can leverage the good faith of someone, of members of Congress,” said Galva. “But the effect is not as strong as actually having a voting voice in Congress. It’s not the same thing.”

The effect on doctors and patients

Because Puerto Rico has minimal funding for insurance, many doctors have left the island in what is being called a “doctor exodus” in search of better pay. According to Marín, the island is losing about 500 providers a year. This is in part because Puerto Rico doesn’t use a fee-for-service model for Medicaid. Instead, a risk-based model is used, which results in doctors receiving lower payments.

“If we have the same rates as Florida, New York, New Jersey, Chicago,” said Marín, “they’re not going to need to go leave the island because they’re going to pay me more there.”

Many medical students who study at the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine end up completing their residency in the States for a variety of reasons. Dr. Tamara Feliciano-Alvarado graduated from UPR’s med school in 2007, and wanted to go to a big city for her residency. She ended up in Boston, and then moved to Pittsburgh to do subspecialty training. Now, years later, Feliciano-Alvarado does think about going back to serve the community she grew up in.

“Even as I started thinking about going into medicine, I had an idea. I had that hope that I could take care of people in my own island where I’m from,” said Feliciano-Alvarado. “That’s always been a little bit of a sad spot in my career, because, you know, Puerto Rico trained me but I am not there.”

Even with all the reasons to go back, Feliciano-Alvarado knows it would be a struggle. With her subspecialty in pediatric gastroenterology, she must always be affiliated with a hospital and she said not many hospitals in Puerto Rico are looking for full-time sub-specialists. Therefore, she would instead need to set up her own practice, which would be incredibly expensive. And since many children with chronic health issues rely on Medicaid, Feliciano-Alvarado would have little guarantee of proper payment.

Even for patients able to get on Medicaid, the doctor shortage is disrupting their health care. It took many phone calls for Carlos Manuel Gonzales-Cruz, a 56-year-old from San Juan, to finally gain access to Medicaid even though he qualified for it. But his struggle to get treatment for an umbilical hernia continues.

Photo by Adarsh Bhat | Carlos Manuel Gonzales-Cruz poses outside of the Medicaid clinic after meeting with a doctor.

Because of the physician shortage, he has seen different doctors every time who don’t seem to grasp his medical history. Some have recommended surgery, others, medication.

To one, he resisted a prescription for more drugs. “I said ‘that’s not normal.’ And she wasn’t my primary doctor. My [primary doctor] is another person,” said Gonzales-Cruz.

With unknown doctors and unknown funding, adequate and consistent health care on the island remains uncertain.

Health care providers have done their best with the little they have but there are lofty goals to make the coverage similar to what it would be in the States. “We have lived with scarcity so long that we are very good at getting the maximum bang out of our buck,” said Galva.

But Marín wants more for her people. It’s only fair, she said.“If we’re going to ask for parity, we need to behave as states. We need to have fair rates. We need to provide quality of access.”