Photo by Kathy Gannett | An original painting by artist Pablo O’Leary, seen here in the year 2000, that demands”Peace and Health for Vieques.”

By Maaisha Osman

CEIBA, Puerto Rico ⏤ When Zaida Torres Rodriguez was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2019, she was forced to commute via ferry and car for two years to the main island of Puerto Rico for her chemotherapy treatments.

A typical transfer involved taking an hour-long boat ride at 6 a.m. from Vieques to the port of Ceiba, followed by an hour-long car ride to an oncology hospital in Rio Piedras, San Juan. Returning home was also an ordeal, the effects of which were harrowing.

“It affects your mental health because chemo is exhausting. It’s terrible,” said Rodriguez, a 67-year-old retired nurse in Vieques and mother of three. “In the first hour, you don’t feel much. But after a few hours, you need to lie down, and your soul can’t take all that wait and commute.”

More devastating, Rodriguez isn’t the only one in her family who is battling cancer. “In my family, my mother died of [liver] cancer in 2019 [at 79],” she lamented. “And my daughter died from leukemia,” she said about 16-year-old Liza Rosa, who passed away on March 14, 1997. Rodriguez now lives with her 70-year-old husband, who has recently survived prostate cancer.

Photo courtesy of Zaida Torres Rodriguez | The Rodriguez family on Zaida’s birthday, April 20, 2022, with her husband, sons Luis Esteban, Miguel Rosa, daughter-in-law and grandchildren.

The Rodriguezes’ story is one of many similar tales of woe that characterize the people of Vieques, a small island in the northeastern section of the Puerto Rico archipelago, home to 8,300 residents and undeveloped beaches with shimmering turquoise water. Wild horses roam the tranquil countryside. Spanish architecture and art influence its small cities, which stretch like a ribbon across 20 miles in one direction and 4.5 miles in the other. And tourists from all over travel to take glowing nighttime kayak rides in bays known to have the brightest bioluminescence in the world.

But living on Vieques is not the paradise it seems to be, especially for people who suffer with serious or specialized health problems. In 2017, when Hurricane Maria tore across the landmass on its way to petering out over the Caribbean Sea, Vieques’ only health center was destroyed, forcing its people into a monumental health crisis. A makeshift health center was established with $4.2 million from the Federal Emergency Management Association consisting of one emergency bay, some prenatal services and dialysis offered in a separate trailer unit. But there is only one emergency doctor and one medical director who operate out of the one-story building.

While the Centro de Salud Familiar Susana Centeno, locally known as Centro de Diagnostico y Tratamiento (Center of Diagnostics and Treatment), was constructed as a stopgap, anyone who needs more than basic care is forced off island. For residents like the Rodriguezes, it has cost convenience, safety and peace of mind. For others, it has led to a high rate of mishaps, mistakes and medical complications, and even untimely deaths.

For example, when 77-year-old Carmen Valencia, a retired teacher in Vieques and a mother to six, grandmother to 14 and a great-grandmother, recently suffered from lower abdominal pain, she went to the health center for x-rays and was advised to see a kidney specialist. Her pain didn’t go away, and she couldn’t find any appointments on the main island of Puerto Rico. Finally, she was rushed to Florida where she was able to see a nephrologist with the help of her daughter, Mildred Masi, 45, who works as a chef at Baptist Hospital in South Florida. Better now, Valencia is concerned about the lack of specialists on the island and stressed that most cannot afford to travel as she did for proper healthcare. “Some people die because they don’t fly on time,” Valencia said.

According to the local government, there are measures under way to correct the situation.

On Jan. 21, 2020, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, earmarked about $40 million to reconstruct a new health canter on Vieques – though as of January 2021, none of the funds had been disbursed by Puerto Rico’s Central Office for Recovery, Reconstruction and Resiliency. Once built, the $56 million facility – Puerto Rico itself must make up the difference in cost – is supposed to contain a delivery room, hyperbaric chamber, pharmacy and a chemotherapy infusion room. There are also plans to have a laboratory, an imaging center, a minor surgery room, a dialysis center, outpatient clinic, dental care and a heliport.

Mayor José Corcino Acevedo is aware of the lack of specialists and proper facilities and the struggle that encompasses exhausting long-commutes to San Juan for treatments.

“Our residents have to lose all day going to the big island to treat their health conditions because they can’t do it here,” Corcino Acevedo said in a statement from early April. Still, the soonest residents will see a new medical center is 2024, which has prompted outrage since they have already been waiting five years.

Photo by Myrna Pagan | Kathy Gannet at a protest in 2016 for cleanup of military contamination in Vieques.

Regardless of such cries for help, some in power, including Edna Marín, director of Medicaid at the Department of Health in Puerto Rico, believe that Vieques should have a facility that encompasses a spectrum of services for the local population, but not a full-scale hospital.

“In the long run, have a facility that can be sustainable, not end up having a huge building that eventually can’t sustain the island,” said Marín.

Outrage, protest and clean-up

As debate continues about how big, and how elaborate, the new medical center should be, another parallel struggle has long besieged the people of Vieques – one they say is inextricably linked to the need for advanced, specialized healthcare.

From 1941 to 2003, the U.S. Navy and NATO allies used the eastern part of Vieques as a testing bomb range, when more than 300,000 munitions were fired during military training operations for members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO. During the Second World War and the Cold War, Vieques and other Caribbean islands served as important military training bases.

Research conducted in the Environmental Conflict Resolution Lab at Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont concluded in 2002 that the U.S. Navy’s testing of live munitions in Vieques also included napalm and depleted uranium, cancer-causing substances the Navy originally denied using on the island but eventually admitted to in 1999.

“The U.S. Navy created contamination to the land, to the sea and to the people of Vieques,” said Gannett, who, like many residents, scientists and researchers, link the military presence on the island for those 60 years to increased chronic disease risk among its residents, which they say has resulted in higher rates of cancer, cardiovascular, renal and neurological diseases, diabetes, asthma and poor infant and maternal health outcomes.

Depleted uranium-tipped ammunitions were first tested in Vieques in 1980; local scientists estimate that somewhere between 300 and 800 tons of depleted-uranium weapons were tested there during the Gulf War. Because of the high temperatures generated on impact, uranium is released in a radioactive cloud. A single particle of depleted uranium can be lodged in the human lung, where it will give off 800 times the radiation considered safe by U.S. regulations.

Testing continued through the ‘90s – until April 19, 1999, when civilian security guard David Sanes Rodriguez was standing outside an observation post as two bombs by the Navy struck on either side of him, 50 feet away. He was killed instantly. Four others were wounded.

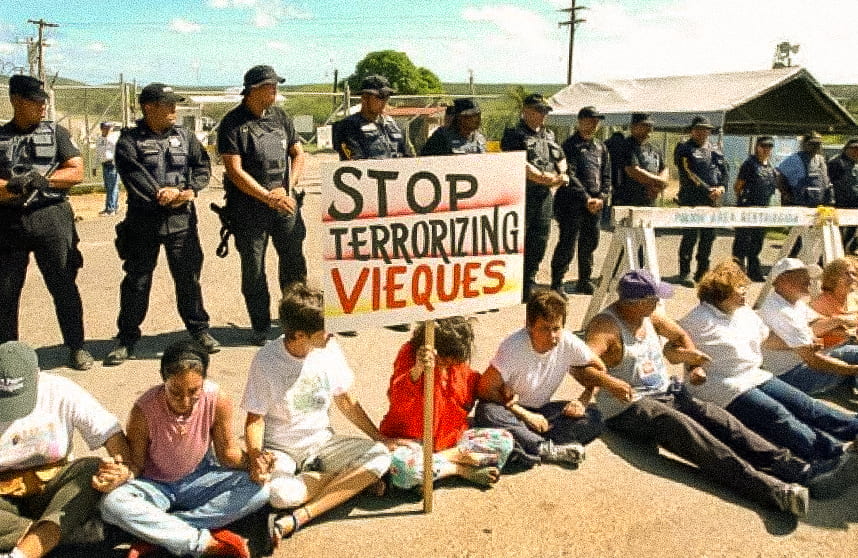

Captions (in order): Photos by Kathy Gannett |Protest in 2018 at the Vieques Ferry Terminal seeking an adequate ferry service; the 10th anniversary celebration of the closure of U.S. Navy Base in May 2013; a protest in 2001 after a 5-year-old Vieques resident died of cancer; a protest in 2001 in front of Camp Garcia to demand an end to bombing practices by the U.S. Navy.

But the damage was already done. In his first study, published in 1999,” Arturo Massol-Deyá, a biologist and conservationist in Puerto Rico, documented high levels of lead, cobalt, nickel and manganese in violin crabs near the Vieques impact area. A second study by him in 2000 found that vegetables and plants growing in some civilian areas were highly contaminated with lead, copper, cadmium and other metals entering the food chain. Another longitudinal study published in 2017 by Massol-Deyá found the contamination was less after the military activities stopped in 2003, but then went up again in 2013 when the Navy “cleanup” of the impact area was put into practice.

“It is not a cleanup. What they are doing is identifying unexploded bombs that they can see with their naked eye and doing open detonation,” said Massol-Deyá. “It’s like adding bombing activities and calling that cleanup – that’s a huge contradiction.”

He added that enormous amounts of soil must be removed to recover lost depleted-uranium rounds. “The technology is there; they refuse to use it. It’s like the life of Viequenses is of lesser value than the life of an American,” said Massol-Deyá.

Photo by Sofia Perez | Arturo Massol-Deyá in Condado, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Cruz María Nazario, an epidemiologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Graduate School of Public Health, noted that there are signs all throughout the island warning visitors not to stray off the permitted paths due to the risk of stepping on an explosive. “If you go swimming you see a bomb in the water,” Nazario said.

The U.S. Navy anticipates the effort will take another 10 years on land, and 15 to 20 years underwater, to clean up the mess. But again, local scientists and activists scoff at this timeline, saying it requires both faster response times and a mitigating plan with a more thorough, expansive strategy.

“Think about the bombs blowing up in Vieques one after another, the components like mercury, arsenic and others don’t disappear,” said Massol-Deyá. Such exposure can contaminate ground water and drinking water and fish or shellfish. In fact, an international tribunal found in 2000 that the groundwater in Vieques has been contaminated by nitrates and explosives.

“The components are no longer in the format of bomb but in different format going into the particles, soil, water systems,” said Massol-Deyá. “That’s when things get really messy, and you don’t have a localized problem.”

The Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC), the current program manager for the clean-up in Vieques, did not respond to an interview request. Christopher Penny, who was the program manager at NAVFAC in Vieques between 1999 to 2011, has refused to comment due to conflict of interest with NAVFAC Atlantic being his client.

“We have the clean-up going on for 20 years now,” said Gannett. “Blowing up the munitions is not a good way to clean up, it is spreading more contamination, but it is equally irresponsible to leave the lands without digging down and taking the munitions out of the land.”

Desperation, but also hope

In the meantime, to address the island’s lack of health services that are compounded by the aftermath of munitions testing, Sandra Meléndez, a long-time Vieques resident, founded the organization Vieques en Rescate or VER. The non-profit was founded in 2013 initially to support cancer patients that reside in Vieques with maritime and terrestrial transportation facilities to reach their medical appointments in the main island.

Currently, VER is advocating for making the ferry experience better for cancer patients. The non-profit proposed that the Maritime Transportation Authority have an air-conditioned space near the terminal where the cancer patients can rest while waiting for the ferry.

VER serves 75 cancer patients on the island who actively use their transportation facility; around 200 patients are registered for their service. The organization also provides residents in need with supplies like diapers and other nutritional supplements, medical supplies, as the island lacks a pharmacy, payment deductibles for medicines, psychological services and educational workshops – a much needed boost for residents, 46% of whom live in poverty.

But nothing that Meléndez does can confront some of the starkest realities present on Vieques.

According to Nazario, for example, people who live in Vieques are eight times more likely to die of cardiovascular disease and seven times more likely to die of diabetes than others in Puerto Rico.

Photo by Sofia Perez | Cruz María Nazario in Condado, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

She added that there is also a high number of infant deaths on Vieques than the main island, pointing to a 2016 study that shows an increase in exposure to bombing activity leads to a 70% increase in premature births and congenital anomalies. She also noted that according to a study released by Puerto Rico’s Health Department in 2003, residents of Vieques were 27% more likely than other Puerto Ricans to have some form of cancer. However, those numbers are likely low, she said, because most cancer patients get their diagnosis on the main island, meaning it’s impossible to track a connection to where they live.

Despite the realities of what life on Vieques might bring to its residents, Gannett understands why people continue to remain there. From the cliffs towering over the ocean and the lush green to the pristine white-sand beaches and turquoise water, it’s obvious why so many are in love with the rugged beauty of the island they won’t ever leave. Which is why she continues to fight for them, and for herself.

Like Gannett, the wondrous ocean right outside Rodriguez’s door helps her escape from the stark realities of her life. Despite it all, she has hope for the future.

“The future generations in our island deserve better services and I don’t want my grandchildren to go through what I have gone through,” said Rodriguez.

“We have to work so that young people of Vieques can study specialties and bring them back to their island. The problem is very complex, but we have to do the work.”